Spring is here and the trees of Brooklyn Heights burst with color. As I walk the sidewalks of Montague Street, the Main Street of Brooklyn Heights, they seem continuously busy, crowded with shoppers with bags and visitors with cameras and MapQuest.

Street level windows often change with the season or new tenants. Today both windows and window shoppers reflect the cheerful weather.

Above me, the rooflines reveal vestiges of the past: a Mansard window, once ornate brickwork, faded lettering advertising the Hotel Montague. Across Hicks Street stands the impressive Heights Casino with a faux Dutch façade of stepped gables whose members still play tennis and squash in traditional whites.

Once a single line trolley en route to the Wall Street ferry below ran past mom-and-pop stores, local butchers and a small Raulston’s grocery—now CVS—symbolic of the suburban life of those who lived in the surrounding streets. Some residents had lived many years in the neighborhood and had seen it prosper, then descend to virtual poverty existence, only to soar in an unaffordable reversal of real estate value.

Looking at Brooklyn’s landscape outside the borders of the Brooklyn Heights, I see a strikingly new Brooklyn climbing to the skies. But the heart of landmarked Brooklyn Heights maintains a serenity with its Victorian brownstones, historic churches and wood frame houses on its side streets.

To walk through Brooklyn Heights is like walking through a history book. Long ago, I worked in television. When I passed through period sets, I was transported back to a previous century or a foreign land. But then the set was broken down, vanishing like smoke.

However, Brooklyn is not a movie set, in spite of all the location trucks on its streets. Brooklyn is real. And Brooklyn Heights is where Brooklyn started.

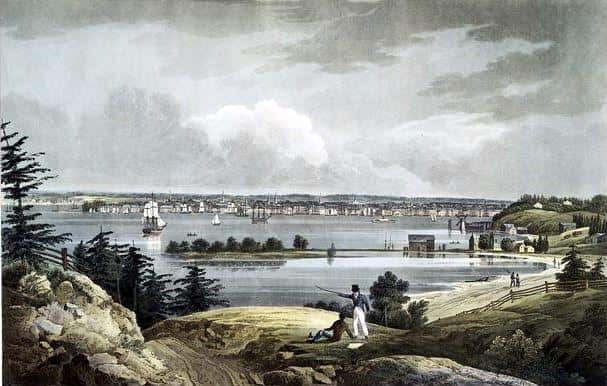

Brooklyn Heights, 1823

Today both natives and visitors find it hard to realize that thick woods populated the area; tall, stately trees dotted the horizon where towers of steel rise today. The residents farmed food, not silicone. And horses plodded over cobbled stone streets.

Vestiges of those days remain where Joralemon Street slopes down to the waterfront and today’s Brooklyn Bridge Park. The mansions of yesteryear, now mostly sub-divided, can be discovered along The Promenade. Until the Landmarks Preservation Law was passed in 1965 saving Brooklyn Heights from developers and Robert Moses’ byways, Gothic brownstones met the wrecker’s ball to be replaced by modernistic substitutes. But many private homes boasting dates of origin survive.

Strolling along Columbia Heights where Norman Mailer once lived, I can observe the street view of magnificent brownstone houses that line the Promenade with an occasional former hotel, The Standish, or an art deco masterpiece interrupting. There, at Clark Street, stands the site of a former Revolutionary War fort transformed into Fort Stirling Park. Continuing past the “fruit streets” to Middagh Street, I pass the oldest house in Brooklyn Heights at Willow Street, built around 1820. In that year, the merchant, Hezekiah Pierrepont, who owned most of the land of Clover Hill gridded the streets.

The street to the east of Montague—formerly Constable Street, named for Pierrepont’s wife but changed for a British relative, Lady Montagu, without the “e”—was a tribute to this original developer. Several architectural gems line this street but the strangest is the Behr House, the former Palm Hotel, Built in the 19th century by a wealthy manufacturer of sandpaper, the Behr House stands on the corner of Henry and Pierrepont. Built of huge stone blocks, it features a broad entrance and four floors with a castle-like aura complete with turrets. After Herman Behr died, the house was owned and occupied by Polly Adler, a madam who wrote about it in A House Is Not A Home. The subsequent tenants were a branch of Franciscan Brothers, a religious order. Then a hotel. Now condos.

Brooklyn Historical Society

Further along Pierrepont Street stands the gothic structure that houses Brooklyn’s past, The Brooklyn Historical Society. The written history of the Heights and of Brooklyn remains sequestered in that awesome building. Look up at the frieze for busts of literary, intellectual and artistic geniuses. It had been The Long Island Historical Society back when residents identified Brooklyn as the western tip of Long Island. Now that we think of Long Island as synonymous with far away East Hampton, the substitution of “Brooklyn” clarifies. The building has stood at that location since Civil war days when Brooklyn Heights evolved as the arts and culture center of Brooklyn. The rectangular building across the street was once the Huntington Club for men but now houses St. Ann’s School.

When I turn the corner onto Clinton Street, the eastern border of the Heights landmark district, I pass St. Ann and the Holy Trinity Church, a refuge for concerts as well as spiritual solace. Around the corner on Montague Street, nestled among the banks and lawyers, were the original Brooklyn Public Library and the Academy of Music. They moved out by the dawn of the nineteenth century allowing new bank construction.

After Montague is Remsen Street, named for one of the early settlers. The former First Presbyterian Church of Brooklyn, now a condo, sits on the corner of Clinton and Remsen. Walk along the southern side of the street and look up at the rooflines of the stately multi-storied brownstones, particularly the white Brooklyn Bar Association building. On both sides of this structure are synagogues, one Orthodox, one Reformed. Continue to the corner of Henry. There stands the site of the original Plymouth Church, now Our Lady of Lebanon Maronite Roman Catholic Cathedral. The heavy metal doors with scenes of the Normandy countryside came from the French liner “Normandie” which capsized in New York harbor while it was being re-outfitted during World War II.

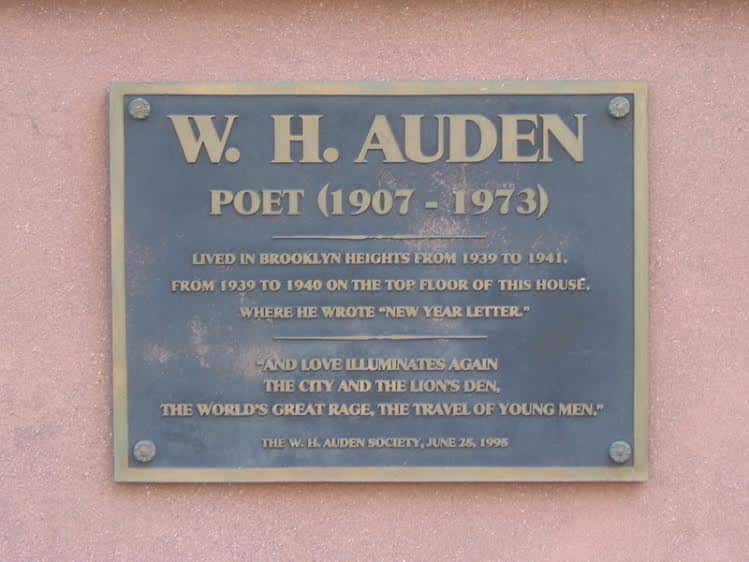

As I walk along Remsen Street toward the East River and The Promenade, I notice red plaques attached to certain houses. The one on the next block commemorates Henry Miller, the scandalous writer who lived there. Two blocks further on Montague Terrace are the former residences of Thomas Wolfe (“Only the Dead Know Brooklyn”) and the poet W.H. Auden. At one point, Arthur Miller lived around the corner on Joralemon.

At the corner of Remsen and Hicks, I look up at the brownstone where the words “Remsen” and “Hicks” are carved into stone under the second floor windows. This remnant from the past helped identify the streets for the 19th century taxi coachman who sat high on his horse drawn carriage.

The end of Remsen Street leads to the entrance of The Promenade with its views of Manhattan, the harbor, the sunsets and Brooklyn Bridge Park below. At the Montague Street entrance, near where the Penny Bridge stood to allow pedestrians to cross the trolley tracks, is a small memorial to George Washington. Prior to the Battle of Brooklyn, he used the mansion that once stood there, as his headquarters. Now visitors gather opposite the park, taking selfies against the skyline.

Because Brooklyn Heights sits atop a palisade left by an ice age, it commands a view of the Manhattan skyline and the harbor including Governor’s Island, which was the original settlement of the Dutch before they moved over to New Amsterdam. Since that original community was restricted to today’s Wall Street area, the wealthy and restless burghers moved to Breuckelen, the wilderness on the other shore of the East River. The rest, as they say, is history.

For a more detailed history of Brooklyn Heights, pick up a copy of Brooklyn Heights: The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of America’s First Suburb by Robert Furman (The History Press) at Barnes & Noble or CourtBooks, both on Court Street.

You can see why Brooklyn Heights has an incredibly fun, colorful and rich history. Experience more of it on our A Slice of Brooklyn Neighborhood Tour!

John B. Manbeck, a Brooklyn native with degrees from Bucknell and New York universities, taught in Brooklyn’s secondary schools and at Kingsborough Community College for 32 years. After two years at Helsinki University in Finland on a Fulbright Teaching Grant, he returned to Brooklyn. Now a full professor emeritus at the college, he taught English and journalism and founded the Kingsborough Historical Society. Brooklyn Borough President Howard Golden appointed him the official Brooklyn Borough Historian and Mayor Rudy Giuliani appointed him director of the advisory committee of the NYC Municipal Archives. He has appeared on the History, Discovery and A&E channels to discuss Brooklyn’s history and has been a member of PBS’s Friends of 13, a speaker for New York Council of the Humanities and a member of the Kingsborough College Foundation Board. For eight years, he wrote a column on Brooklyn history for The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He divides his time between East Stroudsburg and Brooklyn.